If you use source control, you’re on your way towards understanding memory ordering, an important consideration when writing lock-free code in C, C++ and other languages.

In my last post, I wrote about memory ordering at compile time, which forms one half of the memory ordering puzzle. This post is about the other half: memory ordering at runtime, on the processor itself. Like compiler reordering, processor reordering is invisible to a single-threaded program. It only becomes apparent when lock-free techniques are used – that is, when shared memory is manipulated without any mutual exclusion between threads. However, unlike compiler reordering, the effects of processor reordering are only visible in multicore and multiprocessor systems.

You can enforce correct memory ordering on the processor by issuing any instruction which acts as a memory barrier. In some ways, this is the only technique you need to know, because when you use such instructions, compiler ordering is taken care of automatically. Examples of instructions which act as memory barriers include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Certain inline assembly directives in GCC, such as the PowerPC-specific

asm volatile("lwsync" ::: "memory") - Any Win32 Interlocked operation, except on Xbox 360

- Many operations on C++11 atomic types, such as

load(std::memory_order_acquire) - Operations on POSIX mutexes, such as

pthread_mutex_lock

Just as there are many instructions which act as memory barriers, there are many different types of memory barriers to know about. Indeed, not all of the above instructions produce the same kind of memory barrier – leading to another possible area of confusion when writing lock-free code. In an attempt to clear things up to some extent, I’d like to offer an analogy which I’ve found helpful in understanding the vast majority (but not all) of possible memory barrier types.

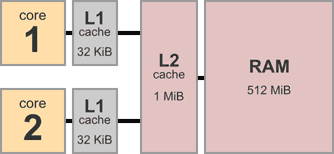

To begin with, consider the architecture of a typical multicore system. Here’s a device with two cores, each having 32 KiB of private L1 data cache. There’s 1 MiB of L2 cache shared between both cores, and 512 MiB of main memory.

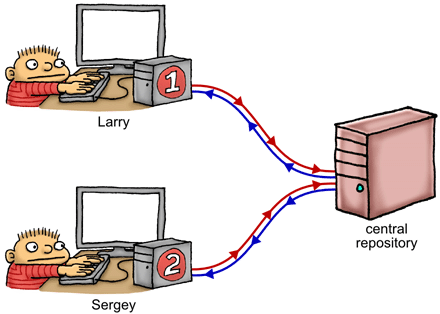

A multicore system is a bit like a group of programmers collaborating on a project using a bizarre kind of source control strategy. For example, the above dual-core system corresponds to a scenario with just two programmers. Let’s name them Larry and Sergey.

On the right, we have a shared, central repository – this represents a combination of main memory and the shared L2 cache. Larry has a complete working copy of the repository on his local machine, and so does Sergey – these (effectively) represent the L1 caches attached to each CPU core. There’s also a scratch area on each machine, to privately keep track of registers and/or local variables. Our two programmers sit there, feverishly editing their working copy and scratch area, all while making decisions about what to do next based on the data they see – much like a thread of execution running on that core.

Which brings us to the source control strategy. In this analogy, the source control strategy is very strange indeed. As Larry and Sergey modify their working copies of the repository, their modifications are constantly leaking in the background, to and from the central repository, at totally random times. Once Larry edits the file X, his change will leak to the central repository, but there’s no guarantee about when it will happen. It might happen immediately, or it might happen much, much later. He might go on to edit other files, say Y and Z, and those modifications might leak into the respository before X gets leaked. In this manner, stores are effectively reordered on their way to the repository.

Similarly, on Sergey’s machine, there’s no guarantee about the timing or the order in which those changes leak back from the repository into his working copy. In this manner, loads are effectively reordered on their way out of the repository.

Now, if each programmer works on completely separate parts of the repository, neither programmer will be aware of these background leaks going on, or even of the other programmer’s existence. That would be analogous to running two independent, single-threaded processes. In this case, the cardinal rule of memory ordering is upheld.

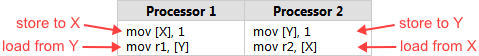

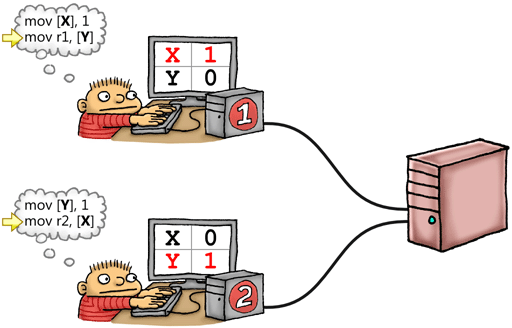

The analogy becomes more useful once our programmers start working on the same parts of the repository. Let’s revisit the example I gave in an earlier post. X and Y are global variables, both initially 0:

Think of X and Y as files which exist on Larry’s working copy of the repository, Sergey’s working copy, and the central repository itself. Larry writes 1 to his working copy of X and Sergey writes 1 to his working copy of Y at roughly the same time. If neither modification has time to leak to the repository and back before each programmer looks up his working copy of the other file, they’ll end up with both r1 = 0 and r2 = 0. This result, which may have seemed counterintuitive at first, actually becomes pretty obvious in the source control analogy.

Types of Memory Barrier

Fortunately, Larry and Sergey are not entirely at the mercy of these random, unpredictable leaks happening in the background. They also have the ability to issue special instructions, called fence instructions, which act as memory barriers. For this analogy, it’s sufficient to define four types of memory barrier, and thus four different fence instructions. Each type of memory barrier is named after the type of memory reordering it’s designed to prevent: for example, #StoreLoad is designed to prevent the reordering of a store followed by a load.

As Doug Lea points out, these four categories map pretty well to specific instructions on real CPUs – though not exactly. Most of the time, a real CPU instruction acts as some combination of the above barrier types, possibly in addition to other effects. In any case, once you understand these four types of memory barriers in the source control analogy, you’re in a good position to understand a large number of instructions on real CPUs, as well as several higher-level programming language constructs.

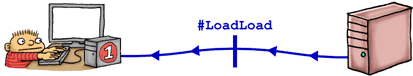

#LoadLoad

A LoadLoad barrier effectively prevents reordering of loads performed before the barrier with loads performed after the barrier.

In our analogy, the #LoadLoad fence instruction is basically equivalent to a pull from the central repository. Think git pull, hg pull, p4 sync, svn update or cvs update, all acting on the entire repository. If there are any merge conflicts with his local changes, let’s just say they’re resolved randomly.

Mind you, there’s no guarantee that #LoadLoad will pull the latest, or head, revision of the entire repository! It could very well pull an older revision than the head, as long as that revision is at least as new as the newest value which leaked from the central repository into his local machine.

This may sound like a weak guarantee, but it’s still a perfectly good way to prevent seeing stale data. Consider the classic example, where Sergey checks a shared flag to see if some data has been published by Larry. If the flag is true, he issues a #LoadLoad barrier before reading the published value:

if (IsPublished) // Load and check shared flag { LOADLOAD_FENCE(); // Prevent reordering of loads return Value; // Load published value }

Obviously, this example depends on having the IsPublished flag leak into Sergey’s working copy by itself. It doesn’t matter exactly when that happens; once the leaked flag has been observed, he issues a #LoadLoad fence to prevent reading some value of Value which is older than the flag itself.

#StoreStore

A StoreStore barrier effectively prevents reordering of stores performed before the barrier with stores performed after the barrier.

In our analogy, the #StoreStore fence instruction corresponds to a push to the central repository. Think git push, hg push, p4 submit, svn commit or cvs commit, all acting on the entire repository.

As an added twist, let’s suppose that #StoreStore instructions are not instant. They’re performed in a delayed, asynchronous manner. So, even though Larry executes a #StoreStore, we can’t make any assumptions about when all his previous stores finally become visible in the central repository.

This, too, may sound like a weak guarantee, but again, it’s perfectly sufficient to prevent Sergey from seeing any stale data published by Larry. Returning to the same example as above, Larry needs only to publish some data to shared memory, issue a #StoreStore barrier, then set the shared flag to true:

Value = x; // Publish some data STORESTORE_FENCE(); IsPublished = 1; // Set shared flag to indicate availability of data

Again, we’re counting on the value of IsPublished to leak from Larry’s working copy over to Sergey’s, all by itself. Once Sergey detects that, he can be confident he’ll see the correct value of Value. What’s interesting is that, for this pattern to work, Value does not even need to be an atomic type; it could just as well be a huge structure with lots of elements.

#LoadStore

Unlike

Unlike #LoadLoad and #StoreStore, there’s no clever metaphor for #LoadStore in terms of source control operations. The best way to understand a #LoadStore barrier is, quite simply, in terms of instruction reordering.

Imagine Larry has a set of instructions to follow. Some instructions make him load data from his private working copy into a register, and some make him store data from a register back into the working copy. Larry has the ability to juggle instructions, but only in specific cases. Whenever he encounters a load, he looks ahead at any stores that are coming up after that; if the stores are completely unrelated to the current load, then he’s allowed to skip ahead, do the stores first, then come back afterwards to finish up the load. In such cases, the cardinal rule of memory ordering – never modify the behavior of a single-threaded program – is still followed.

On a real CPU, such instruction reordering might happen on certain processors if, say, there is a cache miss on the load followed by a cache hit on the store. But in terms of understanding the analogy, such hardware details don’t really matter. Let’s just say Larry has a boring job, and this is one of the few times when he’s allowed to get creative. Whether or not he chooses to do it is completely unpredictable. Fortunately, this is a relatively inexpensive type of reordering to prevent; when Larry encounters a #LoadStore barrier, he simply refrains from such reordering around that barrier.

In our analogy, it’s valid for Larry to perform this kind of LoadStore reordering even when there is a #LoadLoad or #StoreStore barrier between the load and the store. However, on a real CPU, instructions which act as a #LoadStore barrier typically act as at least one of those other two barrier types.

#StoreLoad

A StoreLoad barrier ensures that all stores performed before the barrier are visible to other processors, and that all loads performed after the barrier receive the latest value that is visible at the time of the barrier. In other words, it effectively prevents reordering of all stores before the barrier against all loads after the barrier, respecting the way a sequentially consistent multiprocessor would perform those operations.

#StoreLoad is unique. It’s the only type of memory barrier that will prevent the result r1 = r2 = 0 in the example given in Memory Reordering Caught in the Act; the same example I’ve repeated earlier in this post.

If you’ve been following closely, you might wonder: How is #StoreLoad different from a #StoreStore followed by a #LoadLoad? After all, a #StoreStore pushes changes to the central repository, while #LoadLoad pulls remote changes back. However, those two barrier types are insufficient. Remember, the push operation may be delayed for an arbitrary number of instructions, and the pull operation might not pull from the head revision. This hints at why the PowerPC’s lwsync instruction – which acts as all three #LoadLoad, #LoadStore and #StoreStore memory barriers, but not #StoreLoad – is insufficient to prevent r1 = r2 = 0 in that example.

In terms of the analogy, a #StoreLoad barrier could be achieved by pushing all local changes to the central repostitory, waiting for that operation to complete, then pulling the absolute latest head revision of the repository. On most processors, instructions that act as a #StoreLoad barrier tend to be more expensive than instructions acting as the other barrier types.

If we throw a #LoadStore barrier into that operation, which shouldn’t be a big deal, then what we get is a full memory fence – acting as all four barrier types at once. As Doug Lea also points out, it just so happens that on all current processors, every instruction which acts as a #StoreLoad barrier also acts as a full memory fence.

How Far Does This Analogy Get You?

As I’ve mentioned previously, every processor has different habits when it comes to memory ordering. The x86/64 family, in particular, has a strong memory model; it’s known to keep memory reordering to a minimum. PowerPC and ARM have weaker memory models, and the Alpha is famous for being in a league of its own. Fortunately, the analogy presented in this post corresponds to a weak memory model. If you can wrap your head around it, and enforce correct memory ordering using the fence instructions given here, you should be able to handle most CPUs.

The analogy also corresponds pretty well to the abstract machine targeted by both C++11 (formerly known as C++0x) and C11. Therefore, if you write lock-free code using the standard library of those languages while keeping the above analogy in mind, it’s more likely to function correctly on any platform.

In this analogy, I’ve said that each programmer represents a single thread of execution running on a separate core. On a real operating system, threads tend to move between different cores over the course of their lifetime, but the analogy still works. I’ve also alternated between examples in machine language and examples written in C/C++. Obviously, we’d prefer to stick with C/C++, or another high-level language; this is possible because again, any operation which acts as a memory barrier also prevents compiler reordering.

I haven’t written about every type of memory barrier yet. For instance, there are also data dependency barriers. I’ll describe those further in a future post. Still, the four types given here are the big ones.

If you’re interested in how CPUs work under the hood – things like stores buffers, cache coherency protocols and other hardware implementation details – and why they perform memory reordering in the first place, I’d recommend the fine work of Paul McKenney & David Howells. Indeed, I suspect most programmers who have successfully written lock-free code have at least a passing familiarity with such hardware details.

Preshing on Programming

Preshing on Programming